The Beauty of Existence: The Influence of William Carlos Willams’ Life on his Poetry

Puerto Rican-American physician and poet, William Carlos Williams was a leading author in the imagist movement, a transition in American literature from abstract, Shakespearean-like prose to precise imagery and direct writing styles, during the early 1900s. Through his clear, concise yet clear lines of verse and a keen eye for detail, Williams has helped revolutionize American poetry by shedding light on the value and meaning of even the most trivial moments and conventional objects of common American life. However, many of Williams’ styles and themes may be greatly attributed to his experience as a doctor, life in New Jersey, and Unitarianism beliefs.

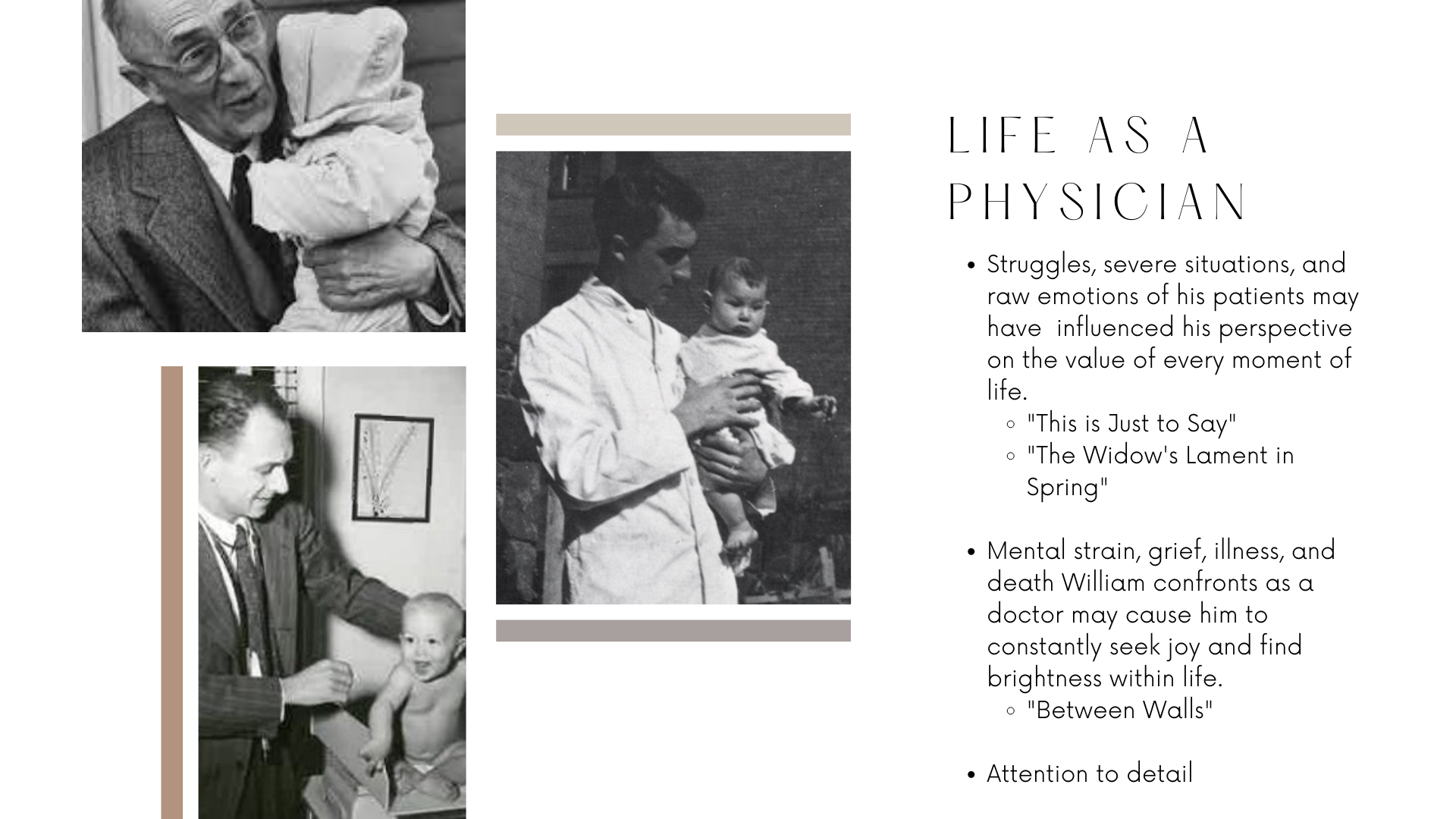

Although remembered for his writing, Williams worked as a pediatrician throughout his career, molding his views on life and hope as well as developing an increased attention for minuscule details. Even during his tireless life as a healthcare worker, Williams still found the time and space to write poetry, in between meeting patients and on prescription blanks. Furthermore, with the struggles, severe circumstances, and raw emotions of his patients still fresh in his mind, these situations may have increased his appreciation and value of every moment of life. In his poem, “This is Just to Say,” the speaker reminisces on plums that were “delicious/so sweet/and so cold.” The vivid emotions derived from a menial fruit, such as a plum, illuminate how meaningful each moment is despite appearing superficially trivial. Williams also develops another layer of depth to this incident as the poem is written as an apology to the speaker’s wife for accidentally pilfering her plums and thoroughly enjoying them. Though the poem highlights the guilt the speaker feels, this emotion also reveals how much the speaker loves and cares for her, as he feels sorry for his actions. Focusing on everyday emotions, such as guilt and joy, the poem may reflect this heightened value and meaning Williams puts behind everyday moments of life, perhaps acquired from his frequent encounters with death in the hospital. Additionally, he may have been inspired to accurately portray the normality of a person’s life during his experience conversing with patients who are typical everyday people; since a lifetime is mostly filled with a cascade of small memories (such as feeling guilty after eating a plum) rather than grand, life-changing moments, Williams exhibited the importance and meaning behind these small moments through his poetry.

Moreover, as a pediatrician who also assisted in the delivery of children, Williams worked at the intersection of new life birthed into the world and the stealing of life by death, perhaps causing him to wrestle with the idea of existence. Since witnessing the death of any loved one, from child to spouse, is able to purloin the joy in one’s life, he may have turned to poetry to express this anguish. In “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime,” he follows the grief of a widow looking at flowers. Though they were once beautiful, the flowers now only remind the widow of her late husband as she reflects that the “grief in [her] heart/is stronger than [the flower’s beauty]/ though they were [her] joy/formerly.” Through the short lines and direct message, this poem illustrates Williams’ desire to portray people’s lives in a raw and truthful manner rather than using poetry as a platform for flaunting bejeweled words. Hence, from his experience with facing the lives of his patients, Williams employs vernacular language (not pampered in complex syntax or diction but rather direct and simplistic) to convey the true, real moments of one’s life as well as the emotions one may face when they are bereaved of a loved one.

Next, the mental strain, grief, illness, and death William confronts as a doctor may cause him to constantly seek joy and find brightness within life. In William’s poem “Between Walls,” he describes that in a hospital where “nothing/will grow,” he notices “broken/pieces of a green/bottle” shining. The use of the absolute language of nothing depicts the sadness and sorrow drenched within the hospital, most likely inspired by his difficult own moments working in a hospital, while the description of the glass glistening portrays a glimmer of hope and joy. William conveys that even amidst the shriveled environment of the hospital, where hope and joy seem to be a fleeting dream, Williams still manages to find bundles of joy in the most unsuspecting objects. This may be a manifestation of the resilience and optimism William obtains from his career as a doctor, working in plague-filled environments. In fact, in a documentary of Williams’ life, he discusses a person does not require “conventionally poetic material'' but instead one can write poetry out of “anything that is felt or felt deeply enough” (Williams Carlos Williams, 1988). The mindset that poetry (and therefore meaning) is ubiquitous and found even in the ordinary may have given him the ability to see hope even within the most stressful times of his life, darkest days in the hospital, and allowed him to find purpose in the smallest moments of his life, hence providing a sense of comfort. Williams’ relentless optimism may have allowed him to capture the signs and meaning of common objects through his writing.

Furthermore, Williams' attention to detail in this poem may also correlate to his medical school experience. From studying at the University of Pennsylvania, earning his medical degree, and working in private practice for over forty years, Williams has lived a life where these seemingly trivial details entail major consequences and failure to recognize them may result in even the loss of a life (Macgowan, "Williams, William Carlos 1883-1963"). As a doctor, his career is supported by his ability to notice and act upon certain details to maintain the health of his patients and during the rigorous medical courses at the University of Pennsylvania, high attentiveness would allow him to maintain his grades and perform well academically. Overall, this skill developed as a part of his career path may have played a significant role in Willams ability to identify and write about precise, imminent details, such as the glimmer of a green bottle—it is simply in his nature as a doctor to take account of them in the first place.

Another key factor that may have influenced William’s writing is his life in New Jersey. In “A Poor Old Woman,” William elucidates the happiness of a woman on the streets as she savors bites of a plum, “[c]omforted/ [by] a solace of ripe plums.” With one of the highest population densities in the nation, his life in New Jersey may have allowed Williams to peer into windows of other people’s lives while commuting to external destinations since public transportation and walking are the most common ways to travel about the city. In his autobiography, Williams even admits that he “walked around the streets [...] and [he] listened to [people’s] conversation as much as [he] could. [He] saw whatever they did, and made it part of the poem” (The Autobiography of Williams Carlos Williams). Seeing these transient moments of people’s lives may have led Williams to explore and write about common life for the common people (as he utilizes simple and short syntax and diction). When writing about the woman eating plums on the street, he showcases the happiness she finds even amidst poverty, illustrating the joy that can be found even in a presumably unpleasant or common life. Additionally, as he watched various other, ordinary people, he may have gleaned insight into their lives as well, witnessing the complexity of each person, and developing a sense of empathy from simply the act of “people-watching.” This idea of bringing attention to people and things often overlooked is expressed in his poem “The Red Wheelbarrow,” as he discusses the beauty of a “red wheel/barrow/glazed with rain/water.” Just as he portrayed the poor woman in an admirable manner, Williams illustrates the wheelbarrow in a simple description of beauty, exhibiting how it transcends the unexceptional appearance and conventional use into one of elegance. Overall, Williams’ life in New Jersey, watching everyday people amidst their separate lives, may have encouraged him to write about the beauty of everyday people and objects often overlooked.

Finally, William obtained unitarianist beliefs which may have contributed to his ability to consistently highlight the positives and beauty in unremarkable things. When describing the woman in “To a Poor Old Woman,” he doesn't depict her in a condescending or derogatory manner but rather conserves her happiness in the poem. Portraying the women, although poor and old, in a positive light is characteristic of the unitarist beliefs of the value and worthiness of every person, regardless of social status or racial background and may also be attributed to the kindness and compassion promoted throughout the religion (Ritchie, "Christianity: Unitarian Universalism”). Additionally, in “Spring and All,” Williams discusses how the stark cold of winter is transitioning to spring since the trees no longer have “dead, brown leaves under them” or are “[l]ifeless in appearance” but rather “grip down and begin to awaken.” This transition evokes feelings of hope and life awaiting in the future of a dark, barren time conveyed through the shift from decaying leaves to the sprouting buds of life. As this poem was written during the end of World War II, it may depict his desire for hope and peace for the future, principles stressed in unitarianism. These beliefs of compassion, life, and peace may have helped foster a passion for highlighting the everyday experiences of common people and objects, realistically capturing their life and emotions.

Through the simplicity of his language and tactful crafting of the syntax of his lines, William conveys the rawness yet splendor of merely conventional existence. As a physician and writer, he symbolizes the intersection of the sciences and humanities, which is echoed through his unitarianism beliefs, and he uncovers the magnificence of daily life from people-watching in his hometown of New Jersey. However, from serving as a pediatrician, healing and delivering infants to the world, to a poet, portraying common experiences and objects in a remarkable manner, Williams never fails to be a reminder of the value and beauty of life.

REFERENCES

Cutler, Kirsten. "A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams." School Library Journal, vol. 54, no. 9, Sept. 2008, pp. 199+. Gale General OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A185487106/GPS?u=tlc201825818&sid=bookmark-GPS&xid=a6a61ae5. Accessed 23 Feb. 2023.

Lowney, John. “The Ethics of William Carlos Williams’s Poetry” William Carlos Williams Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 2014, pp. 95–98, https://doi.org/10.1353/wcw.2014.0005. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Macgowan, Christopher. "Williams, William Carlos 1883—1963." Edited by A. Walton Litz and Molly Weigel, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1998, pp. 411-433. , link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX1380200028/GLS?u=tlc201825818&sid=bookmark-GLS&xid=d53021ef. Accessed 27 Feb. 2023.

Ritchie, Susan. "Christianity: Unitarian Universalism." Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, edited by Thomas Riggs, 2nd ed., vol. 1: Religions and Denominations, Gale, 2015, pp. 344-354. Gale In Context: High School, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CX3602600039/GPS?u=tlc201825818&sid=bookmark-GPS&xid=43aa5619. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Rogers, Richard P. William Carlos Williams. Voice and Visions, South Carolina Television Network, 1998. https://youtu.be/Du1DJli1_jY Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Schumacher, Peter and Christina, Petrides. "William Carlos Williams." Poetry Criticism, edited by Jonathan Vereecke, vol. 206, Gale, 2018. Gale Literature, link.gale.com/apps/doc/JYGKNG322472357/GLS?u=tlc201825818&sid=bookmark-GLS&xid=e2b483bb. Accessed 23 Feb. 2023.

“William Carlos Williams Papers.” Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, 15 Dec. 2009, beinecke.library.yale.edu/article/william-carlos-williams-papers. Accessed 2 Mar. 2023.

“William Carlos Williams | Poetry Foundation.” Poetry Foundation, 2022, www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/william-carlos-williams. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Williams, Williams C. The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams. Cambridge, MA: New Directions, 1967.

Williams, William C. “Between Walls | Poetry Foundation.” Poetry Foundation, 2023, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/49849/between-walls. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Williams, William C. “The Widow’s Lament in Springtime by William Carlos Williams - Poems.” Poets 2019, poets.org/poem/widows-lament-springtime. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.

Williams, William C. “To a Poor Old Woman by William Carlos Williams.” Poetry Foundation, 2020, www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51653/to-a-poor-old-woman. Accessed 26 Feb. 2023.